The “behind-the-music” myth is so familiar it risks losing its edge: the genius album, the fraying relationships, the push and pull between ambition and creative endurance. But Stereophonic — David Adjmi’s Tony-winning play with music, now at the Hollywood Pantages Theatre through Friday, January 2nd, 2026 — makes that familiar narrative feel startlingly alive whether or not it borrows from tensions underlying Fleetwood Mac during Rumours.

Set inside a 1976-77 California recording studio (Sausalito and then Los Angeles), the nearly three-hour production invites audiences into the messy, intoxicating, and often punishing crucible where above-the-fold art is shaped. Its Broadway triumph remains historic with thirteen Tony nominations, the most ever for a play, and five wins including Best Play. On tour, the work retains its shattering clarity and magnetic pull.

Though the plot never leaves the studio complex — which is inclusive of a live room, control booth, and a cramped lounge where emotions slosh over the rim — the world feels vast. Over the span of a year, a rising rock band attempts to finish an album that could define their careers. Every technical decision becomes personal; every personal wound reverberates through the microphones. What Adjmi captures so vividly is the way artistic labor and emotional instability feed one another as inspiration sparks conflict, conflict sparks brilliance, and brilliance demands a toll on top of already obstructive character flaws.

This national tour is particularly gripping because of the cast of seven’s ability, notwithstanding their proficient singing and/or legitimate playing of instruments, to seamlessly inhabit Adjmi’s world with both an explosive volatility and a quiet exhaustion embodied by artists working at their limits, intertwined with the intermittent relief of levity.

As Peter — the genius guitarist, arranger, and producer — Denver Milord artfully presents not only an inspired take on Lindsey Buckingham, but that of a man whose obsessive micromanagement, even at the cost of becoming verbally and physically abusive toward his bandmates, is nothing more than an overcompensation in the face of a personal mess threatening to engulf him. Cursed by his upbringing, or own willful doing, Milord’s performance is layered insofar the audience’s sympathy for him never entirely extinguishes.

Claire DeJean, as lead vocalist Diana and seemingly a proxy for Stevie Nicks, provides much of the production’s emotional ballast. Her vocal purity and interpretive finesse make it instantly believable that the band potentially needs her more than she needs them. More importantly, DeJean’s acting charts the incremental drain of navigating undue pressure to hit all the right notes, made all the more cumbersome when she is endlessly pushed and prodded by the man (Peter) who is supposed to love and support her the most. Ultimately, Diana, self-conscious as she is due to not playing an instrument at a high level despite writing songs, discovers an epiphany about her worth — an exclamation point that DeJean thoughtfully, not haphazardly, arrives at.

As Reg, the band’s charismatic but disheveled bassist, Christopher Mowod is a standout. His Reg is magnetic and maddeningly absent-minded, encapsulating a man capable of being a consummate professional one moment and being besieged by his addictions and insecurities the next. Although he does a fantastically funny Baby Face Nelson impression, Mowod resists caricature; his persona’s ego never overshadows the fragile humanity underneath, infused by a philosophical outlook suitably wrapped up in the statement, “We must love life.”

From Reg’s perspective, what fuels much of his malaise is his roller coaster romance with Emilie Kouatchou’s Holly, the group’s keyboardist and backup singer. Kouatchou gives a beautifully modulated performance, characterized by a softness that gradually hardens, evolving from being a “shy little girl” to one who fends against a destructive relationship. Like DeJean’s Diana, Kouatchou is afforded moments to set her character apart — which she embraces in full — one of which includes a fascinating take on the irresistibility of Donald Sutherland vis-à-vis Julie Christie in the 1973 film Don’t Look Now.

Representing the rhythm section is Cornelius McMoyler’s Simon, the normally laidback and voice-of-reason drummer who sporadically finds himself wrestling with internal storms, whether it’s the realization of not having seen his kids in a long time or feeling judged for his ability to keep time. McMoyler’s subtle physicality — evinced via the tightening of his shoulders and even the way he takes out his vexation on the drum set — underscores a deeper complexity in Simon, who nonetheless still exhibits a silent strength, than gleaned at first sight.

Young lead engineer Grover is portrayed by Jack Barrett, who adeptly weaves his “background” persona around the big personalities in such a way that Grover, and the confidence that grows out of the weight of his opportunity, becomes indispensable to the narrative. Grover’s experience is equivalent to the audience’s perspective — quietly watching, sometimes with staunch patience, looking ahead, and reacting with very human emotions at a tableau that is restless and far from glamorous.

Last but not least, nearly stealing the show on a few occasions is Charlie, the assistant recording engineer, depicted by Steven Lee Johnson whose quirky and random characterizations are handsomely disbursed with impeccable coming timing. One notable instance is a story about a country singer in Nashville who becomes institutionalized — it’s conveyed with a superlatively uproarious mix of naïveté and obliviousness.

Director Daniel Aukin, returning to the production he shepherded on Broadway, has calibrated every beat with forensic precision. Scenes begin in casual overlapping banter before breaking down into arguments. One moment of harmony evaporates when an out-of-place critique is uttered or when a tape is recorded over. Through it all, however, the pacing never drags. Instead, the repetition, be it failed takes, looping disagreements, and half-finished apologies, creates an accumulation of pressure that mirrors how albums are actually made. It’s like watching an award-winning documentary.

The music, composed by Will Butler of Arcade Fire fame, is embedded into the play’s fabric with masterful authenticity. The performers themselves not only become a live band (never mind the mere “illusion”), the songs sound like plausible, Fleetwood Mac-esque 1970s rock tracks, with head-nodding riffs and hooks — imperfections and all. We hear them in fragments, but it’s the piecemeal construction which gives the final musical breakthroughs — the most appropriate examples being “Masquerade” and “Bright (Take 22)” — genuine catharsis.

Technically, the touring production is remarkably faithful to Broadway. David Zinn’s set places the live room and control room in constant visual dialogue, allowing audiences to watch inspiration and aggravation ricochet across the glass. The disarray, represented by cables and slouched couches, feels lived-in rather than theatrical. Jiyoun Chang’s lighting is at times sumptuous and then duly meager, dimming the box within which this visual diary is thoroughly laid out.

Ryan Rumery’s sound design, which scored the Tony in his category, is not only aurally immersive, it differentiates between rough monitor feeds, in-progress mixes, and euphoric playbacks. Dialogue remains astonishingly clear, a feat in the Pantages’ cavernous space. Enver Chakartash’s costumes avoid retro parody but rather conjure a genuineness through soft denims and color without oversaturation.

The three-hour journey, marked by periodic self-indulgence, will be a dividing line, but it is also central to the play’s effect. Stereophonic unfolds like the arduous recording process itself: iterative, incremental, frustrating, and occasionally transcendent. The play respects its audience enough not to fully resolve its tensions but insightfully share messages on the pros and cons of sacrifice in a communal setting where collaboration, not egocentrism, yields timeless contributions to the arts.

In a season abundant with holiday spectacles, Stereophonic arrives as something richer and more unsettling with its visceral, unguarded portrait of the creative process at its most combustible. While it’s not a musical, the songs are heavily ingrained in the play’s identity and, at the Pantages Theatre, where the scale amplifies both intimacy and chaos, the production becomes a full-body experience as theatregoers can, second by second, experience the exhilaration and fallout of chasing greatness, note by note.

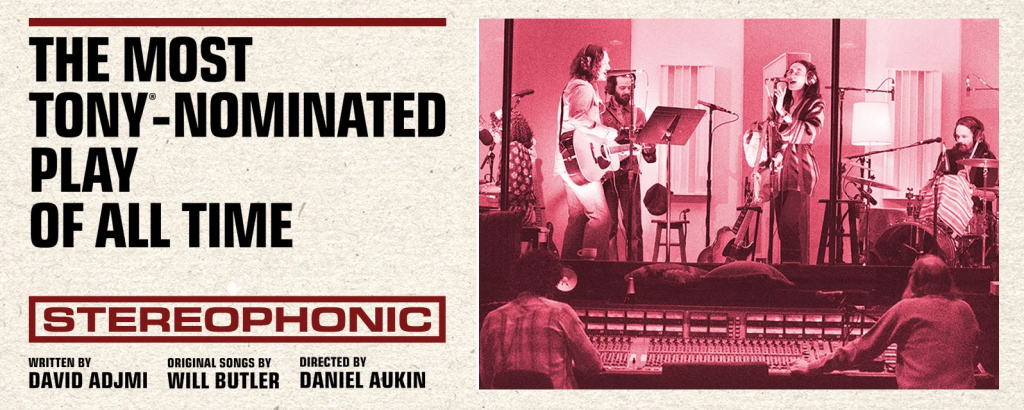

Cover image caption: The cast in the national tour of Stereophonic. Photo credit: Julieta Cervantes.

Stereophonic runs through Friday, January 2nd, 2026 at the Hollywood Pantages Theatre. For more information on the play and to purchase tickets, visit broadwayinhollywood.com.

When I go to the theatre, I go to for entertainment. I don’t go to interpret how the characters I am watching are representative of an actual band. I was out of the country for most of the 1960s and 1970s, so I am familiar with the music of Fleetwood Mac, though I am not familiar with all the dramatics in their personal lives. That said, my experience at Stereophonic at the Pantages was that it was a complete disaster. I walked out at the intermission regretting the 90 minutes I had wasted. I like Fleetwood Mac’s music but the abominable sounds called “music” in this production IMHO bore no resemblance to the music of Fleetwood Mac. The mixing was atrocious with the drums and guitars completely overwhelming the vocals. The music reminded me more of punk or grunge than Fleetwood Mac. The British accents were hard to understand especially in the couch areas on stage left and right. The voices in center stage around the mixing console were hollow and echoy like they were talking in a cavern. The story made no sense to me but like I said, I am not familiar with all the personal lives of the members of Fleetwood Mac. Perhaps the play redeemed itself in the 3rd and 4th acts, but I was ready to leave after the first 10 minutes.

I completely agree with Lee. It was awful – the music was terrible, the mix drowned out the vocals, the English accents were atrocious, and the plot was slow-to-non-existent. It bore no resemblance to the actual process of recording an album, or to the story of Fleetwood Mac. We also left at intermission.